Solipsistic Americanism passes through London and makes itself international, sort of.

- Fernando Herrero

- Nov 13, 2023

- 57 min read

Updated: Dec 8, 2023

By Fernando Gómez-Herrero.

I attended The Future of Capitalism in an Age of Insecurity Conference (lse.ac.uk). It opened with a plenary by Daron Acemoglu (MIT) on Friday on the technological and AI innovation business side of things. Saturday was the main day with three panels under the headings of “Globalization and the Return of Geopolitics,” “Populism and Democratic Capitalism,” and “Global Governance in an Era of anti-Globalism.” Your eyes will see “global” repeated three times, perhaps four with the prefix “geo.” These are current soundbites. Did geopolitics ever get out of the stage? How is our global moment different from the one that follows the 1990s? Does anti-globalism mean economic nationalism? Does it mean mounting challenges to U.S. supremacy? Would populism be a good or a bad word as one Italian speaker put it? Would democracy ever go beyond electoral politics? What does the term do to or with capitalism? We are navigating diverse “cultural” varieties (American, European, Chinese, Russian, African, Latin American, etc.) and there will different affiliations and vested interests. This conference put America first.

These are momentous questions and thorny issues, to be sure. The event was chaired by Peter Trubowitz who directs the Phelan United States Centre at LSE. So, no surprise: the bald eagle had a nice place to stay in London in this quick passing. There was no need for translation or interpretation between Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers (“you say potato, I say potato,” as the Aljazeera Palestinian senior commentator Marwan Bishara, who was not in this conference, would put it in relation to an ongoing war in the Middle East). This was a ‘happy’ Anglo bubble and for all the unsettling nouns in the titles of panels, I did not sense a lot of trepidation. It was as though the speakers were making the most of a certain home-court advantage. There was more uncanny familiarity than challenging foreignness, let us say.

The panels took place in the open-space of the Great Hall of the Marshall Building in the central London site of the LSE by the Holborn tube station (or is it subway?). It was an open event that required prior registration but no strong security was needed. The incoming new President and Vice Chancellor Larry Kramer gave a few opening words in the opening of the second day. The predecessor went the other way to Columbia University in what is hegemonic North-Atlantic Anglophone corridor of “global” academia. Kramer’s trajectory passes from NYU, Stanford and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation (About Us (hewlett.org)) before reaching London. These connections probably continue. His quick words did not touch on geopolitics, but on the early vision of a super-hub with Oxford and Cambridge, LSE and UCL. Praising London as the most international place on earth, the joke was on the New Yorkers who would probably object. The general discourse was going to be moving towards how capitalism survives its upsets, how AI technology changes and generates transformations and how geopolitical crises pile up, but the US stays on top and how to make capitalism more inclusive, pursue growth and economic security, its negative sides were excluded from the conversations. Whose ‘victory’? One must assume that of the social groups of those directly involved and, by extension, their institutional networks and societies, the U.S. taking pool position, Britain dutifully following suit. The conference was a “special relationship” of sorts, with the blessings of LSE, John Phelan philanthropy (Introducing John Phelan (lse.ac.uk)) and the Hewlett Foundation.

Emphasize the “positives” and make things projective, enterprising, “optimistic,” without lingering on the “negatives,” signal but never develop the achievements of the “competitors.” This was an all-American gathering at the levels of who was and was not on the platform, the type of discourse, explicit referentiality of administrations, Biden’s, a professed desire to “lead,” not loudly trumpeted, but unmistakable. In more ways than one, the gathering was a bit of an infomercial for global capital, American style. The general tone was one of “Yes, there are some issues out there but also great opportunities. We are challenged in our leadership, but we continue to lead. We need to make some adjustments and everything will be all right, etc.” The conference demonstrated the blindness and insight, the darkness of the renaissance, the barbarism of civilization, a naturalized monolingual provincialism befitting the one-eye superpower. The Americans –and I am a U.S.-passport-carrying variety type stranded in the UK while writing this account-- were talking to each other and a background of the world that never quite managed to come out of the bald eagle’s nest and say a thing or two in favor or against. We were thus serviced a world picture in which the U.S. is carved out of its totality somewhat, the part becomes the whole and the whole assumes a subordinate, abject part, a res extensa without res cogitans—incapable of deviation and challenges worth their salt. The joke remains: the Americans go overseas to Americanize themselves. I do not recall one single instance of a xenophilic openness to intellectual or emotional foreignness, surely the latter is an excessive category for all of us.

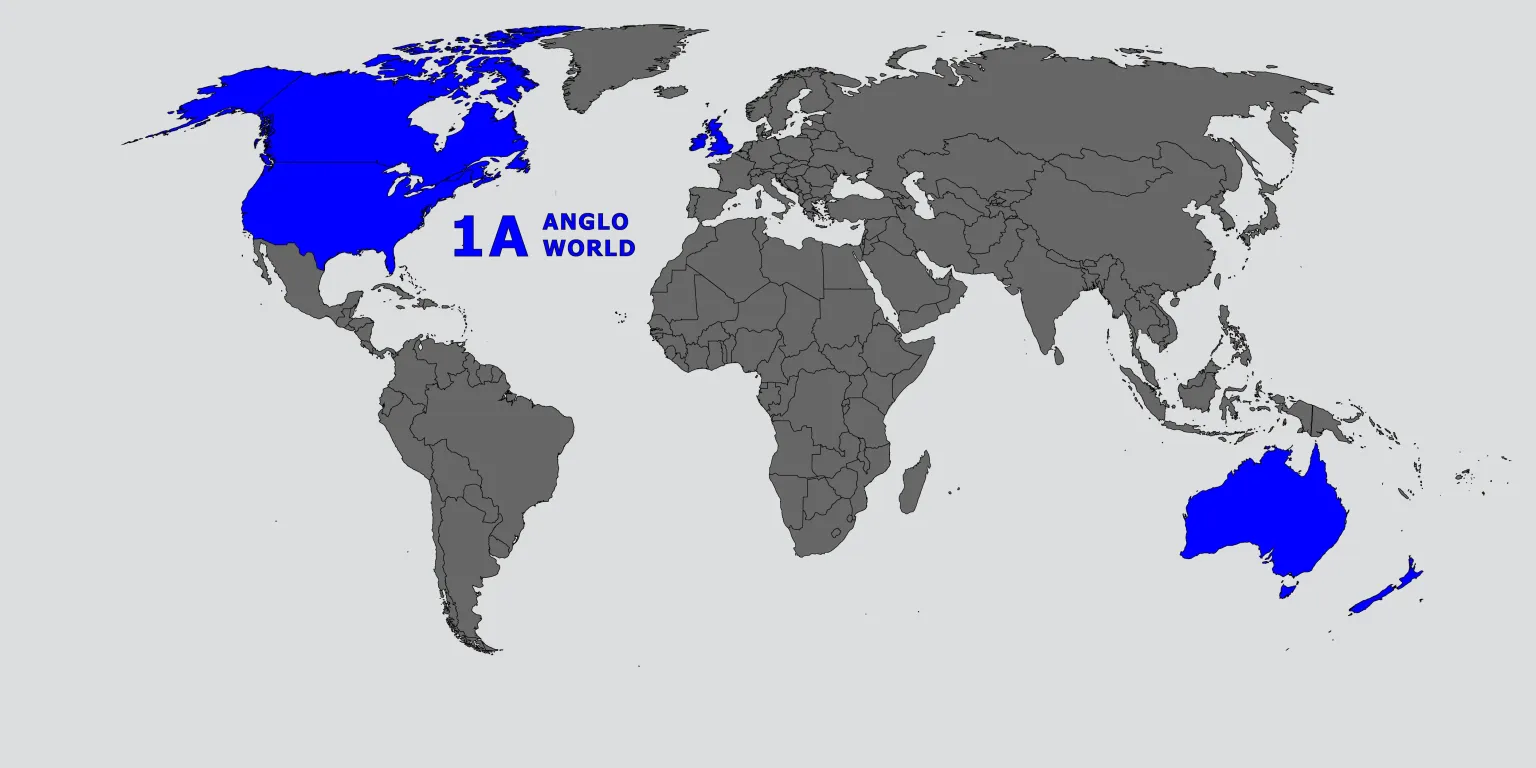

This was a controlled environment inside the Anglo Zone in which foreignness did not interfere with the proceedings. There will be videos and transcripts and some soundbites to be sure. My eye caught some native British varieties being interviewed in the margins. Yet, the participants were exclusively American -if not born and bred, certainly professionally based, with the exception of one African LSE faculty who talked about what else but Africa. Did I perhaps miss any representative of the non-Anglo world? A strict methodological nationalism was in play and we will soon see references to economic nationalism not enthusiastically endorsed by the bulk of participants. I could not make out a Republican-leaning participant on the platform and perhaps there were some in the audience. We were all rowing along collaboratively in the vicinity of the Democrat-administration with the recognizable names of Anne Marie Slaughter and G. John Ikenberry. Jake Sullivan, the United States National Security Advisor, was mentioned more than once. If there were dissenters in IR affairs, “realists” or otherwise, they kept to themselves during these two rainy world-cup-rugby October days which saw a crushing defeat of England, and two great Southern-Hemisphere teams not represented here fighting for Paris, with one African team winning; the U.S. does not play serious rugby and you can read something into the analogy). There were quick references to the “Global South,” a monstrous amalgamation that has emerged in the last few years. The core was the ‘Global West,’ i.e. the U.S. and its allies, in this preferential order. But the nervousness went “global East.”

All eyes were almost exclusively on the impetus of American society, its nation-state apparatus, military-industrial complex and multi-national business might reach informing LSE collaborations. All other societies were very tangentially referenced if at all. The fingers of one hand kept count of the other societies mentioned. Silences, or better omissions, were thunderous. All alliances were imaginatively wrapped up here, but not specified, around the finger of the philanthropic ogre as Octavio Paz called it in the 1980s. We were in the big-business side of political and social things going along the state superpower of long reach. All other nation-states were like creatures of a lesser deity who needed no care or attention. Agency and mind were all-American and the force went mostly one way, unidirectionally, externalizing itself out there with no specificity and there was never, as far as I could see, give-and-take. I do not recall one strong single critique of U.S. state malfunction in the last few decades in relation to any of the participants. Why did I show up for this thing? I wanted to see the latest news of some figures I have known for some time. I wanted to see other names and see what the interaction were. I wanted to see what type of gathering was taking place by Holborn tube station in central London. I would not say I was terribly surprised by what I witnessed. In essence, there is no plan B to American supremacy, which is not to nuanced into big business and state power, academy and mass media or popular culture. These were all presented in collaborative fashion. The world may be burning, but London was not. The hosting was generous. We were nicely fed in the intervals. Rain was mostly falling outside for most of the weekend.

The Brits were not platformed. Old-time and young LSE IR faculty members were sitting in the audience in the front rows and the graduate students sitting in the back. Doctoral-candidates were showcasing their projects and they were standing in front of these during the intervals. Those projects echoed the internationalist and enterprising language of the conference. The old continent was once or twice mentioned in the second position well over all others. The occasional invocation of “Europe” was unclear: the generic term may mean the EU, NATO, it may include the UK or not at all, and all those things were wrapped up in the noun. The feeling was, to me at least, that such Europe is a not so close horizon of American interests. Yet it remains instrumental force multiplier of American interests (the so-called “allies”). At a time of disintegration of historical Eurocentrism, there were no European voices whatsoever here. Brexit Britain was not mentioned and somehow the London metropolis may indeed wiggle out of its limitations. There were no representatives of China, Russia, the “global South,” although these were the big entities alluded to. There were no Anglo experts of these big entities either. There was one representative of a collaborative India. One Indian faculty via a noted Washington university who resold globalization. Predictably, Latin America was invisible woman of the allegory of solitude. There were no references to the Middle East (the conference took place during the ongoing Israel-Gaza war). Russia’s War in Ukraine was alluded once or twice in passing as though things were here clear and nothing else needed to be said. Not for the first time in London and not for the first time in LSE, Ikenberry was given the spotlight for the provision of the global vision that went largely uncontested. There was “art display” in this social forum among our social scientists, who are not known for aesthetics. Jorge Martin was “scribing the event.” I will make one passing reference to him in closing and I will also add some thoughts that came to me while walking around King’s Cross Station about the language of “care” splashed over “global” places. In matters of foreign affairs, it is always about the projection of “optimism” onto the near future.

The moment is unnerving. People in high places appear to renounce at least publicly the neo-liberal capture of capitalism (i.e. de-regulation, or what is called “liberalization” starting from Reagan / Thatcher). But “globalization” creeps in in the 1990s and it is unclear whether the constant use of “global” means something fundamentally different, whether the wings of the bald eagle have been clipped and the flight is now less ambitious, as it shifts from the solid nominal polysyllable (globalization) to the shorter adjective (global), so to speak. I feel it is not and some speakers were quite open about “re-selling” globalization to the general public. Others were more cautious in the vicinity of some statements by Jake Sullivan soon to be included. Kramer equated “capitalism” (always something like a swearword in the American idiom) with “free enterprise,” which a solid presentation card in high places, mind you. You add “free” and “liberal” to pretty much any noun and it automatically becomes more agreeable and palatable at least in some quarters such as those where we were near Holborn. These “good” adjectives also signal the speaking-subject perspective or predilection without further need of context or development, apparently (the same goes with “values,” but this language was here not abused, thankfully). From this organizational angle, it was mostly about the “genius” of capitalism (free enterprise) to go along its various changes and transformations, troubles or hiccups in the pipeline or challenges in the supplier and the ally-and-friend networks. The gathering was invited to take a look, but it was not a close look. “Reform” was invoked and “revolution” too, the former in relation to the big picture, the latter in relation to industries of relationship and care. I imagined P.R. in multi-national corporations rather than picket-line solidarity, union-boss embroglios, unemployment crisis, immigration and ongoing wars. There was something like a bit of bell-tolling in the air apropos what has been called the American dream or the American century.

IMAGE 3: New York Times Magazine (Nov. 29, 2016). Photo illustration by Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari. Map: Rand McNally.

What about the Anglo Zone (i.e. U.S. and U.K.) in the interregnum inside a general crisis of the “liberal West”? That is my phrasing and the quoted terminology is official (the geopolitical capture of Western civilization is always according to general U.S. interests). No participant wanted to entertain thoughts moving into or away from American supremacy or hegemony. America was an amalgam: it meant the state-superpower apparatus, the international-reach philanthropy of capital accumulation provenanced in the U.S., the reach of its higher-ed institutions, etc. There were general references to a desire for a greater distribution of capital as it is now trapped inside increasing ecological limitations and clusters of mounting problems. The emphasis was on some type of control, but it was not unanimous, and “resilience” was a term that came up. It was the first time I heard “resiliencing” within the international setting of great fragmentation and volatility. Those seeking for the “whodunnit” would run into the names of three or four big nation-states or collective units (US, EU, China, Russia, India and “global South,” the nomenclature of BRICS was alluded, disparagingly). The fifteen-minute presentations could not provide rich idiographic specificity, but here are some highlights.

I liked the no-nonsense approach of Michael Mastanduno (Darmouth College) and I liked the India representative, Raja Mohan from New Delhi, who presented an agreeable version of India leaning more towards the US and by extension the West than anywhere else. Mohan distanced himself from Kishore Mahbubani during the coffee break. Apparently, the Singapurian leans too heavily on China who he sees as the future over US and the West for our Indian scholar’s predilections, which is music to American ears. Mastanduno was direct: rather than policy, it is politics and the big noun, geopolitics, the one that has everything to do with capitalism. Directly stated, the geopolitical foundation of capitalism is American, and by extension Western, which is the bright side of the Moon all the participants were contemplating. So, this is the top modality that is now unsettled. This is the adjective-less “insecurity” alluded to in the title of the conference and this is what will be addressed, lightly, publicly, always optimistically speaking. The thrust of the conference was clear: to buttress such leadership, to pull through, to keep leading. There must have been some skepticism among some audience members if one considered earth demographics inside which the “liberal West” (as the conventional social sciences have it) is but a portion, and a declining one, and not the totality of the world picture. The gathering inverted the part-and-whole relationship: the part was totalized, the U.S. was phantasmatic carved-out space, and the whole was pushed into a gloomy corner of the back of the mind with no discourse, vistas, different futures.

There is backlash against globalization and not in name only and not only by those in the trough, Mastanduno mentioned. Trump is one name that came up a few times among those who are taking advantage of this type discontent that may be called “anti-globalist.” The US geopolitical strategy of the integration of China into the world economy has not worked as planned, Mastanduno told us. If the idea was to make China richer, more market-oriented, more like “us,” yet subservient to American interests, a ‘responsible stakeholder,’ America’s ‘junior partner,’ such was the consensus of the last 25 years passing from Bush 1 to Bush 2, this is no longer the case. Why would anyone assume the perennial subordinate position, especially those big and sophisticated, millenarian civilizations? Such incorporation has not worked. China is accused of being less “pluralist” and more “belligerent” (the first charge is a puzzling one in relation to the colossal population dimension of China and the second really means no compliance with U.S. wishes). Mastanduno was giving us a quick critique of the old thinking that preceded 9/11, when the world was –apparently-- going America’s way and time was, unlike the Rolling Stones’ song, on the U.S. side.

No more. Decline was not mentioned as such, but it was implied in the proceedings. So, one subtitle of the conference could be “Dilemmas of Decline” and I am recreating Ian Hall’s good book about British decline post-WWII. Declivity might be too cute a word in relation to a gradual sliding down in the world, but we are talking about such process also in relation to the perceived severe deterioration in U.S. domestic politics, institutions and general popular culture and social media (I am writing these lines after the two-week empty-chair of the Speaker of the House, being occupied by a Trump ally and the mass shooting in Maine). Mastanduno is a straight-shooter: China represents a very unusual type of challenge for the U.S. Unlike the Soviet Union, its economy is deeply embedded in the global economy and there are profound implications for “globalization.” How are you going to compete with, fight, try to contain or carve out a space different from such a colossal dimension? The official discourse remains one of efficiency, resilience, securitization, localization, near-/friend-shoring. It is hardly poetry to the ear but beautiful language is not the point. Mastanduno was the first to refer to the discourse of Jake Sullivan in the Brookings Institute (https://www.youtube.com/watch?reload=9&v=A2sa-p2whkk; Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on Renewing American Economic Leadership at the Brookings Institution | The White House). It provoked rippled effects for the rest of the sessions. This “unapologetic case for national security economism” is a “wrecking ball to the liberal order” (Ikenberry’s ears must have pricked up, which neither affirmed nor negated later). This Biden-Administration disposition is the new orthodoxy: what is good for the [ailing] US economy is also good for national security and vice versa (playing with the famous line “what is good for General Motors is good for America). But there is tautology in this equation between economism and national-security, which does not extricate knowledge production, and the reality is that the global assembler, China, the lowest end originally, is no more. No language of (existential) threat was heard. It was competition instead.These Americans, among whom I did not detect one single China expert, China held no references to politics, language, literature, culture, civilization, religion, social customs, etc. Like superstitious people are said to behave when they do not want to wake up the bad spirit, Xi Jinping was not mentioned once.

“We have not been here in 200 years,” Mastanduno said and this statement gives you the conventional historical horizon of our social scientists. The logic of this history: the great powers are the engines of growth and we go from one to the next inside the shorthand of the UK and the U.S. It is great-power as imbricated with or pushing “global capitalism” and the advertised “shared prosperity” is now undergoing perception of U.S. decline and superpower insecurity. Jake Sullivan’s speech is an enthusiastic embrace of economic nationalism that is targeting Europe as well as other areas or regions (again, by “Europe,” we must understand the European Union qua large market, the UK being a smaller, adjacent and complementary market of the same European platform, at least from the American standpoint which this LSE conference naturalized). The UK minus the EU is less inevitable, from American interests, take London out and add the UK military capability and the European Anglo side of the Atlantic is back on the table as it follows suit. The LSE conference was an example that if not the entire nation of nations, the metropolis must still follow suit, add Oxbridge. Mastanduno’s questions are real: 1/ do these economic-nationalist policies work?, do they generate growth or create more inequality?; can governments pick “winners”?; 2/ can the economy be made “safe” for an attitude of economic nationalism?; can economic nationalism be moderated, mitigated?; 3/ what about the “global South” (the recent euphemism for the former Third World)? Would Jake Sullivan subsidize these members too? The phrasing gives away Mastanduno’s skepticism.

The official slogan of the Biden administration is “a foreign policy for the middle class” as Jake Sullivan did not fail to mention in the aforementioned speech. Are we talking about state-intervention and provision of subsidies? The pithy retort is that “we are not allowed to talk about free trade anymore:” Mastanduno brought attention to the current “over-correction” in American economic strategy (it is a rhetorical device to add the prefix to something the speaker dislikes). Reagan and Thatcher went too much in the direction of deregulation and non-intervention, and we are now, apparently, going, the other “excessive” way, of state intervention and the implementation of controls, at least according to Mastanduno (“social-democracy” is not American idiom, but I suppose that this is the implication). States may get too unapologetic, too over-enthusiastic, etc. “Too” and “over-“ are, in this style, “bad,” from the speaker’s point of view. Unspecified happy medium then. But we are not there yet, always according to Mastanduno.

Raha Mohan gave us a nice vignette about the Number-One and Number-Two economies. The best student (China) of the teacher (U.S.) is now mounting the greatest challenges. Why is the hegemon (U.S.) trying to change the system? Because it is not working for him. Isn’t capitalism built according to the logic of globalization or expansionism? Now, if and when globalization does not benefit a large number of American people, it turns out they want to go against such globalization. Biden / Sullivan are trying to bring Americans back from a disinterest in foreign policy and they do so with those jobs for the middle class (incidentally, Labour’s shadow foreign affairs David Lammy is copying the formula and adjusting it to British tastes). With a gentle touch, Mohan mentioned that inequality has declined in the Global South. “To the guy (U.S.) who was imposing globalization on us, [we say] thank you very much!” Yet Mohan did not see a declining West and a rising East. There were deep differences within the latter, and probably within the former, although he was not going to be addressing the former. What is in crisis is the liberal Western capitalism model, and the leading country (U.S.) is trying to coopt sections of the Global South to stay on stop. Idem, Chinese capitalism, always according to Mohan.

The general vision was one of the broadening of US alliances in dealing with the threat of a rising China (“threat” in so far as it challenges US supremacy, that is). Less or gradual liberalism and more coercion if and as needed: Mohan seemed to be occupying this space too and with him the virtual totality of the platformed participants. The crucial question, “who can co-opt better the interesting sections of the Global South?” I asked him about the verb in the coffee break: it seemed to him more like a gentle push and seductive complementarity rather coercion or brute force. Western decline? Mohan quipped that it has been declining since Spengler in 1901 (Anne Marie Slaughter will pick this up later). Where is Europe? Already in relative decline and it is greater than the American variety, said our smooth-talking, elegantly bearded and bespectacled Indian representative without dwelling too much on the “malady.” About the re-centering of globalization, Mahon did not see an ominous singularity but a proliferation of diversified capitals. The model of the old multinational organizations was not going to work. The way to go: like-minded coalitions. It is a point dear to Ikenberry at least at the slogan level. Echoing Sullivan’s elegant figure of speech in the Brookings Institute: the “global situation” does not look like the straight-lines of neoclassical architecture (say, the bipolar world, the Cold-War Berlin-Wall), but is instead uneven, misshaped, surprising like Frank Gehry’s architecture. Sullivan did not call these forms “postmodern.” But we can add that too. The LSE Phelan US Centre conference lacked such insights in terms of the arts and the humanities. One sorry scribe will show up in the end.

Anne Marie Slaughter has moved from interventionist internationalism under the rubric of neo-Wilsonianism to something one could call a corporate-minded promotion of care and relationships. Our former Princeton figure in government from 2009-11 and 2011-15 (Obama administration), as she reminded the audience (she did not mention that she was a strong ally of Hillary Clinton), prefaced her comments with a reference to Europe, “always in decline, more important to the U.S. now than at any other time.” I wish she had elaborated on that on such central-London platform. It is indeed the horizon of Europe, or rather the European Union with the strong nations of France and Germany sorely missing in action here, the non-negotiable American constellation, Slaughter’s and others. Where else would they go? Hence, witnessing the growing divide between Europe and the U.S. at least since 9/11 and the Iraq/Afghanistan war is agonizing. The entire conference is one effort to put money and discourse to bring the two sides of the “pond” closer together across the North Atlantic. But this is no longer the main theater.

Slaughter was not going to do demanding geopolitics anymore, let alone breaking new ground, compared to her facilitations of neo-Wilsonian vistas two decades ago from the Princeton platform. In the cold shade of great power competition, which she equated to geopolitics, she wanted to highlight geoeconomics instead. But she is no economist. So, hers was a set of well-honed skills of salesmanship. She is now more of a promoter of an economy of “care” for the corporate world, although the ideal subject position never comes out onto the light and is never made clear, neither are the best spaces for intervention or visibility. I suspect that the Gaza strip, the Texan-Mexican border, anything happening on Asia or Africa or Latin America are unlikely options. Women’s education in Afghanistan? Learning English in El Salvador and Spanish in the Bronx of New York, perhaps STEM or vice versa? One never knows.

At any rate, she felt no need to provide a convincing cognitive mapping of the big international world out there and that was probably the point. The point must have been closer to a fudge on the international domain, but always agreeable to American interests and enjoying a bit, why not?, the good time and the shopping in the London metropolis. Say anything you want but the former high-ranking Princeton administrator knows how to address an audience. We may be passing the page, but not quite: Slaughter made a reference to the NYTimes foreign affairs journalist and author Thomas Friedman, the “apostle of globalization,” and one with a knack for successful formulas such as “the world is flat” Gehry’s architecture forms are anything but “flat” (Ikenberry did the same “slumming it” with Gideon Rachman, FT foreign affairs columnist, and it must be a friendly creation of a habitus in the Anglosphere). Yet, there were long shadows stretching inside and outside the Anglo bubble.

True: there is some push against the early globalization typified by Friedman although it is not clear if our new phase is one of murky or hybrid globalization with or without greater protectionism (the “p-noun” is implied; the language of “free trade” has gone soft and we are exposed to the corporate language of “inclusivity” and multi-national “care;” the “old language” of social-security or welfare is not in the vicinity). The conference gave out a feeling of a kind of a desire for community without collectivism, of “economic nationalism” indeed without recourse to the impossible terminology of “national socialism” (socialism is taboo language in the American idiom and rare indeed in the mass media in contemporary Britain except as term of abuse). The rigidities of the American idiom speak of “Christian nationalism” and “alt-right nationalism” as unacceptable or “radical” varieties of political antagonism, at least from a “liberal” standpoint, and the general ethos would not call Ikenberry’s profession of internationalism, nationalistic, which is what it is in the modality of American-superpower supremacy.

Corporate interests seek the collaboration of the U.S. empire (the latter term was obviously not heard in the LSE conference, it is too frank, it is leadership instead). And the U.S. empire –or leadership-- seeks its connections and stretches its tentacles in the different corporate networks and industries, including the “soft power” of its popular culture. Slaughter mentioned that “near-shoring” (“ally-or-friend-shoring”) started before China and the pandemic. She made a reference to the high visibility of the Arab Spring during “Clinton,” she skipped the “Hillary,” and how such global politics anticipated issues of climate, environment, epidemics, floods, etc. She invoked a sense of vulnerability, more in connection with Covid than China and put in our minds a picture of a young Sullivan in the (Bill? Hillary?) Clinton administration and what he was hearing at the ground level, which was that the U.S. was in domestic distress and correspondingly of the lack of interest in foreign affairs. Hence, it is no surprise that we are dealing with the new mantra that “foreign policy has to serve domestic interests.” “Those industrial jobs are not coming back” and the challenges are growing in relation to global warming, migratory flows, floods and fires, etc. As though looking from afar, Slaughter’s manner is feelingly “humanistic,” if I may put it that way, in Bill-Clintonesque-and-Bidenesque-mush fashion, although the term was not used during the conference and is never used in conventional American idiom. She may feel the cosmic pain but she will tough on China.

By such “humanism,” one could smell a ploy, as it is coming from one of the advocates of the Iraq War, and former right-hand woman for Hillary Clinton’s more realist than liberal internationalist or perhaps both in one. Slaughter spoke of “putting people first and ahead of technology.” The vision is, “what can we do?” We love simplicity particularly of diction. The category of “people,” or “humanity,” says it all and says it well. Slaughter is no techie either. She advocated the minimizing of geopolitical competition –me too?-- and the maximizing of other good things. She is about the “well-being economy” and she alluded to existing alliances (Wellbeing Economy Alliance (weall.org)). The simple sentence: “to put technology at the service of humanity” is about the “care economy” Four aspects were mentioned: child care, elders, home, house management. Our 65-year-old baby boomer, CEO of New America, disclosed her age and a future prospect near the equation of “care” and “economy,” in the next decade or two. We must add “the relationship economy.” I am not being entirely facetious but this type of psychological lingo reminds me of the Steven-Pinkeresque style (cognitive psychology, popular-science author, public intellectual, happiness-highlighting popular best seller) morphing into the character of Paula (Vicki Berlin Tarp), the head of personnel in the luxurious yacht of Triangle of Sadness (Ruben Ostlund film 2022), who instructs her team to smile and obey and look friendly and inviting and a handsome payment will come in due course.

We are talking about “coaching,” and it is now everywhere, unlike in Slaughter’s youth, when in the world of sports, super-corporate coach Slaughter told us. For example, teachers are more into personalized learning. There is also an epidemic of loneliness, disconnection and isolation. Without missing a beat, we were told that there is a “care + relationship revolution,” which is also conducive to “good domestic policy.” It is not even the good-cop / bad-cop approach. It is something like the technocratic-institutionalist specialist massaging the message of and to the aggressive executives out there who need to learn a trick or two to relax in between sessions and keep going. We may imagine something like a TV-Series Succession visualization to the LSE setting in highly pressurized Ivy Leagues-with-Washington connections and its international outlets in the UK, EU and elsewhere –and thank god for the nice getaway in London town that allows some quality down time after one or two talks.

The day after the Ivy-League premiership must find its focus on the care-and-relationship service economy. I hesitate whether to call it therapy. There is a hint of catharsis or perhaps ataraxia, but there was “passion” and aplomb in the talk and there is comfort in the comfort zone, at least for those who can afford it. The mind never veered away from the “safe” American shores. For all the nervousness in the air, “The Future of Capitalism in an Age of Insecurity” Conference did not deliver unpleasant, but eminently comforting thoughts (Ikenberry closed down with an “optimistic note” that was appreciated by all, including the facilitator). We may imagine something like the ethos of the fashion magazine of the Financial Times now under the acronym HTSI, more in line with the times [i.e. “How to Spend It”]. Something of this abbreviation was detectable in the conference at large (i.e. focus on the ideal, nominal “inclusion” rather than the massive exclusions all around the Great Hall of the building of the U.S. Phelan Centre at LSE, speak less of “free-trade” and “neoliberal globalization” and insert some concern about domestic dilemmas, and these were American dilemmas and American concerns, without ever dreaming of giving up American leadership in the whole wide world).

Somehow, I did not imagine Slaughter making her care-and-relationship ways through the favelas or the maquiladoras, giving inspirational talks to educators in the Bronx and Queens in New York or El Paso, Texas, addressing cultural concerns among the migrant workers of different colorations informing the latest bus arrivals to the blue states claiming a big sign of welcome. The whole thing felt privileged and phantasmatic as little or nothing was ever landing in unspecific timespace. Were we in dystopia, utopia, heterotopia or was it U.S.A. abroad but for a short amount of time? It sounded new-age-y enough and it may well be a substitute –decaffeinated, fat-free, environmentally friendly, all the good things promised by the advertisements in the London St. Pancras Train Station areas of gentrification-- for what other societies and older times might have called religion. What Alain Finkielkraut did for fashion and philosophy on the European continental court, we may find it now here in modulated enunciation in Anglo-American IR settings short of poetry or philosophy: the well-being cultural industry comes to the rescue in our times of uncertainty and it has no problem dovetailing with foreign affairs. The “barbarians” are mostly outside your imagination.

We were told that there is another “revolution:” multi-generational living of an extended biological family. In a passing criticism to Biden’s binary of “democracy and autocracy,” Slaughter underlined the precarity of the millennials for whom “everything that they think they know is now shifting.” No one is “set for life” anymore. Not even “coding” is safe now with ubiquitous AI looming larger every day in the ominous horizon. So, the idea is –soundbites will never leave us alone—"copilot AI” whilst creating “family values.” In so doing, we will bring conservative sectors onboard. Just when you thought humanism was winning: this may be another way of “co-opting” parts of the Global South, India was mentioned. A final anecdote by the quick-and-seemingly-comfortable-talking Slaughter, “when [David] Patraeus asked India to choose between being a proper member of the Quad and Russia, the answer was, choose? Yes, we choose India!” So it ended the suggestive amplification of the human potential.

How to square this service economy and the U.S. seemingly going down the path of economic nationalism and its tensions, is not obvious to me. We were supposed to be making an internationalist stance in London. But we were not going to get into specificities or details. Yet, there is re-entrenchment, ideological and otherwise, and it certainly speaks to something that is in the air, London included. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA, INFLATION REDUCTION ACT: INFRASTRUCTURE IMPLEMENTATION RESOURCES - National Governors Association (nga.org) was mentioned. To Europe, the message may already have been “pick your market” as a way of shoring up allies (there are Rumsfeldian echoes of the old and the new Europe in relation to the Iraq War). The Pacific Basin may be the flip side within the system of traditional alliance of the U.S., such “traditionalism” must now be supple. And no one here was going to admit to the type of negotiations taking place in the current administration (Ikenberry speaks of “allies” of the like-minded but always stops in the nominal isolation of an open-ended ghost plurality). We may be in some third chapter to two previous chapters: FDR’s New Deal (post-WWII) and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society (1960s, Civil Rights Movement). We can call it the post-9/11/Iraq War Debacle -Bush2 onwards (playfully referred by Mastanduno as “shrubs”). The unnerving moment is one of Biden and Trump making a come-back and even if you had been sleeping for the last three decades, who would want to follow blindly Uncle Sam. Europe must have a relationship with China if Trump comes in or if he doesn’t. The how-to is not clear. Antagonism surfaced: Slaughter mentioned that China does not have a policy to take care of each other (how is that for a belligerent monstrous generality!) and she added another noun to “care:” which one? “Connection.” Mastanduno underlined the fact that small and vulnerable nation-states would rather not want to choose between the U.S. and China.

A good initial joke by an amiable and soft-spoken Mohan: Britain was to the EU what India is to the BRICS, i.e. to prevent the big collective from being effective. His talk was frank and unthreatening, endearing. This was about a collaborative, Western-bound India, surely a monstrous category on its own, keeping its distance from China. Will this be the case, I wonder. Yes, there is a return to “mercantilism,” the atypical word conjuring something like the “badness” of state intervention which is now making a comeback under the rubric of “economic nationalism” (the conference was manufacturing something like an epistemic consent according to an all-American platform model of presentation that is more typical than one would imagine in London think tanks). Plural hermeneutics is not something we witnessed at The Future of Capitalism in an Age of Insecurity Conference (for one thing, all the nouns were in singular). Are we in some replay of the 1930s as a mass-media and academic fashion had it a decade or so ago? In so saying, our imagination flies to continental Europe exclusively, but the world is bigger. The answer was “no” and the MAD-nuclear dynamics may play it differently now. Perhaps the Ukraine situation confirms such dissimilar state of being for now. There was no elsewhere to the US explored with tact or gusto: most speakers were talking mostly about the U.S. for the benefit of the US and by extension, I suppose, its allies, including here Britain, although it was not automatically clear. When it dawned on some of the speakers that we were on this side of the pond, they extended the same findings over here. Europe was no forward utopia but something like comparable heterotopia of minor differences in a usable past and it held dystopian features. The U.S. was the exclusive symbolic space of big origin and teleology. I found it lacking in warmth and winning intelligence. Yet we were all in the grasp, if not the thrall of Uncle Sam who held preserve of power / knowledge. This LSE conference made it clear that there were no worthy competitors out there generating other epistemes.

Slaughter advocated coalition building. The care sector could include start-ups, Wall Street, parents, etc. It sounds like a broad church (something like “care for all, relationships are good,” and that reminded me of the chilling “languages for all” in the British universities). The attempt may have been to echo the language of a certain feminism bringing attention to the crisis of care in American society. But the abbreviated, slogan-language did not allow or afford much of anything. It is devised not to say too much of anything and adjust according to the different audiences and circumstances. I can see Slaughter delivering the same talk to any of those potential coalition-building partners without having to change much or anything. At the end, Slaughter mentioned that the next version of the dot.com economy will have to reflect the fact that the U.S. will not be a white majority in the near future, and also that it must “reflect” the whole world (yes, that was the verb!). With 35% Hispanic population, such was the percentage given, at least some connections in the U.S. will have to go to Latin America, instead of the stronger or more conventional US-EU links, also the thickest texture of economic flows. Mastanduno added an unnerving coda: the contemporary situation reminds him of the 1945-50 phase in the Cold War, when the U.S. and the Soviet Union, like the U.S. and China now, were not consolidated, and one superpower or the other could easily stumble into a conflict that no one wants. The missing Chinese representative added nothing in this regard.

The second panel handled populism and its relations to democracy and capitalism. We were serviced broad brush strokes and some of these were insightful. Sheri Berman (Barnard College) understood populism, she said, exclusively in the right-wing variety. And yet she mentioned that there is a Right/Left convergence given the brand dilution in politics, a concomitant increasing voter de-alignment and growing electoral volatility. Brexit was mentioned, but not developed. Berman underlined the lower education / lower income variables of these voters as markers, signs or opportunities for right-wing actors during times of growing precarity such as now. Ian Shapiro (Yale) started by juxtaposing policy and politics in relation to the big structural changes taking place in global capitalism at this very moment. He dipped in both and he sounded to me like a good Democrat strategist with a modicum of penetrating free-thinking. In the West, we are witnessing a shift to the service economy inside deep levels of globalization, with or without re-entrenchment and protectionism, changing demographics (always a passing euphemism for the de-whitening of US populations, i.e. Latinization), aging populations, etc.

There is also a massive shift underpinning our generalized economic insecurities: twenty-thirty years ago, it used to be one employer for life, it is now 12-15 times when you will shift from one employer to another, full-time job was a one-time job life situation and we are now in the constant job-change pattern, even downgrading from full time to part-time and the embarrassment and rage that go along with it. Shapiro broke down the Trump voter by wages (1/3 less than 50K household; 1/3 50-100K household; 1/3 about 100K per household). The population that feels insecure is not in the margins of society. It is in the unhappy middle and it is a lot of the so-called “middle class.” Such seemed to be the flotation line of society of predilection and this is the one that is sinking and with it the unionized constituency, also hemorrhaging voters. There is an increasing fragmentation of splintered Left/Right (sub-)groups. Shapiro’s tone was calm about some of the “pathologies or sclerosis,” as he put it, in multi-party coalitions when these are not ideologically adjacent. He mentioned Germany. I thought of Sánchez’s Spain, which was probably far from everybody’s mind except perhaps one ‘scribe’ who will show up later. Shapiro defended the Great-Society coalition he sees in the Biden administration. His final strategic suggestion was to shift from identity politics to economic insecurity for the Left-of-Center of American politics. It was picked up by the two other speakers in the same panel, not in terms of abandonment but in terms of emphasis.

Luigi Zingales (University of Chicago) gave some comments that lingered in the air after the conference. He struck me as a brave, independent thinker who would not let his institutional affiliation and thick-Italian accent interfere. He put himself in the crosshairs in the bonhomie anecdote with the step-daughter and LGBTQ+ bathrooms in university settings. He told her that previous generations fought for Civil Rights, Vietnam War and that her generation was fighting for toilet use. The step-daughter came back the next day and said “o.k. you are a white, heterosexual European male but you may have a point.” Zingales poured cold water on the notion of “green economy” in relation to the Biden administration in what felt a partial rebuke to Shapiro. It had to do with the re-admission of factory workers who have become unemployed. Those massively disrupted by big job losses are now undergoing some re-training, but these “green” options only represent a third of the total job losses.

Two steps forward and one step backward or vice versa? Maybe we are tiptoeing backwards to a post-1945 “social welfare” horizon and maybe “out-of-control capitalism” is a bad thing, Berman added. I missed a clear demarcation of the subject position and a concrete timespace specificity in the assertions. Tellingly, there was a critique of elite identity politics done on the cheap (the LGBTQ+ toilet anecdote aforementioned). Zingales mentioned that this is done almost as a consumption good and that it plays differently in the large population, which is now occupying a big hole of uncertainty or a yawning space of precarity compared to Ivy-League elite settings which included the vast majority of the platformed speakers. “I can be super woke and my wallet, full,” Zingales said. “Corporations love it!” Zingales expressed a benign mea culpa about elite reproduction, almost scanning the room and coming from the “coastal town” of Chicago, as he called it benignly, because of the lake proximity. Unconventionally, he defended the “goodness” of populism, which he understood to be the government of the majority of the people. The term populism does not have to be ideologically marked, he added, but it is, and the consensus was that it was some form of anti-elitist disposition that was bringing trouble to all the nouns in the conference title. The call to arms was “it is the economy, stupid:” if this is not done, there will be another Trump after this Trump, and another one.

Shapiro reiterated his respect for the Biden administration which is trying to build a Greater-Society. He mentioned that the last two wars (Iraq and Afghanistan) were paid on debt and how Republicans who do not want to raise taxes, also run on debt. Shapiro took us back in time with a surprising analogy. He equated Martin Luther King and Malcolm X to today’s split on the center-left. The former represented the “rub of the nose of elite hypocrisy,” a broad-church coalition building, and the latter represented the “multiculturalism” (such was the term used by Shapiro) and the recognition of separateness and fissure opening. Shapiro was with the first option. The troubling statement is that the Right is better at identity politics than the Left, he added. “Inclusive growth” must be understood to be good business for elites too, his final line.

Post-lunch, and the lunch was good, the third and final panel brought the notion of “global governance” to the arena of the serious trouble in an era defined as “anti-globalism.” Your reading skills must be good to continue identifying the desirable position of the conference (i.e. the first term, global governance, is good as long as it is the U.S. purchase; the “negative” term, anti-globalism, is figuratively thrown in the direction of those challenges to U.S. supremacy). “Optimism” was invoked, surely conventionally in this type of social-science-cum-business collaboration on a projective international platform.. The third panel title is the type of phraseology that is dear to Peter Trubowitz, whose recent book, written with Brian Burgoon, is mostly about the fractures of the Western Liberal Order. This is not the only game in town and it is not the end of history, although no one in this crowd thinks in terms of philosophical metaphysics. We are not in the Huntingtonian clash of civilizations circumscribed by religious belief-systems. We are instead in the Ikenberryesque line of thought of simplistic tripartite divisions and flexible alliances, at least in this conference. What is at stake is the slowing down of the deterioration of the singularity of American hegemony, i.e. the unipolarity the U.S. had in the 1980s-1990s, which is good for business, but whose. “One of the world’s leading scholars of IR,” such was the introduction of Leslie Vinjamuri, who now appears less active at the less active Chatham House.

Ikenberry gave the feeling of being comfortable in a small graduate seminar which held no fundamentally dissenting voices. The panelists remained seating. Ikenberry checked his notes from time to time. There was no novelty. The essence of the delivery has already come out in the latest book that I have analyzed elsewhere (FGH, 2022). There is also a conversation I had with him, excerpts of which are available here (Liberal Internationalism for Hard Times: An Interview with G. John Ikenberry | Toynbee Prize Foundation). Time is on whose side: there is a previous engagement with anti-Wilsonianism and war that includes both Ikenberry and Slaughter (FGH, 2010). Ikenberry was likely to be the core message of the conference and it was largely in agreement with the Biden administration. Our IR scholar admitted that the Western-led order is troubled and that “the supply of government is declining.” The singularity of “order” –“world” is dropped for calculated reasons, cunning or cuteness—is now open to the plural form that is not of the liking of Ikenberry et al: we can imagine different future orders. Sameness is American supremacy. There are “differences” now but these significations within the Anglo geopolitics of knowledge production are not to be encouraged, say.

Pertinent questions were posed by Ikenberry: 1/ can US and China find terms of coexistence?; 2/ what is the future of liberal internationalism, the school that he represents?; 3/ who are the thinkers, the visionaries, where are the green shoots? I think he mentioned Cordell Hull (FDR’s Secretary of State). He mimicked people saying “who?” If it was not Hull, another one in a similar Democrat administration of consequence would do. The search is always, for Ikenberry, in the arcana of official Americana, i.e. among the most capable civil servants in the situation room. Ikenberry leans for general inspiration on the Democratic administration of greater consequence and it will be in such locus amoenus where he will find a usable past to project the future he would like to see happening (from Wilson to FDR to Johnson, tiptoeing on the still living Presidents of Clinton, Obama and now Biden, Carter is a no-no). Such official America is the sole preserve of future knowledge. Internationalism is the monopoly of the U.S. state apparatus, Democrat-leaning, in what is undoubtedly an obscene demonstration of an epistemic nationalism which is supremacist belief system (i.e. America first and there is no plan B, or in the humorous expression, my “mother [nation], drunk or sober!). In other words, “order” is in so far as the “world” is “ordered” by a superpower that must ineluctably be, thus the article of (secular) faith, American only, add “allies” at will. Russia’s war in Ukraine and the U.S.-China competition have shattered such illusory singularity of one world constructed according to U.S. unipolarity (no attendant made any reference to Israel’s war in Gaza; silence was thunderous).

We were entertaining these world-order questions. Ukraine is not unifying the world according to U.S. predilections, Ikenberry dixit, but he was not going to develop the plurality of those deviations. What was clear for him is that the non-U.S. world will not provide good answers to more desirable futures. The nationalistic methodology at play firmly in Ikenberry will not let go. It is of the narrow IR discipline as manufactured inside Ivy-League gardens of knowledge production. Democratic-Party leaning. Such non-interdisplinary and narrow-provenance methodology effectively means the generalized xenophobic repudiation of the epistemic knowledge capacity of the non-U.S. world, including that of the “allies.” This LSE conference delivered no foreign knowledge production whatsoever that may have tickled the imaginary funny bone of a possible improvement in world relations. Here, foreignness never articulates anything meaningful about the history of the totality of the world, let alone its divergent futures moving away from U.S. hegemony (I always have the impression that Ikenberry deliberately avoids “hegemony” not to enter into Robert O. Keohane’s territory, not to mention that of Antonio Gramsci). Our American IR scholar will not be caught alive engaging with the likes of Agamben, Carl Schmitt, Chomsky to name but three intellectuals of three different nationalities. African, Latin American, Asian scholars are not his interlocutors. His Europe is echo chamber of res extensa of Uncle Sam’s ego cogitans and his U.S. exclusively of the IR discipline as it moves exclusively in Anglophone environments. What type of “world” are we talking about? Ikenberry remains monocultural, monolingual with occasional visits to these US-protected settings in rarified English outposts. There will be comparable others.

Yet I play the ball and not the man who is a diligent scholar who flies over the big picture of the world to see what’s next in one or two decades. The disposition of this propaganda fidei of US supremacy is to see what is best for it in the immediate future in what looks like a re-shuffling of world groupings. Here Ikenberry, perhaps unsurprisingly, leans on Gideon Rachman, foreign affairs columnist of the Financial Times (Culture Fudge in the Anglozone: Gideon Rachman's "global west" (sic, in lowercase). (fernandogherrero.com)). The quality paper is a good tight rope of North-Atlantic mediation, with or without Japanese ownerwhip, straddling London and New York City (add a few world capitals, those fashion sites covered in the fashion magazine of the paper, and one gets the “Western” constellation that matters to our two men). Thick-brush and journalistic-friendly, maximizing intelligibility, I suppose: ours is a three-unit template of Global West, Global East and Global South, all furnishing their own narratives of globality and order, grievances and reform agendas. One gets the emphasis on “global” even in the era of “anti-globalism,” and post-1990s-globalization Friedmanesque boom of “world-flatness” when things were irresistibly going American one way and one way only. West, East, South: no North of the compass. What is the essence of the content of these simplistic and manageable partitions? What is the function? Who-said-it first? Whodunnit? Three big, if dissimilar portions of the world, like a big cake, according to the cutting knife held in tandem by Rachman and Ikenberry. They are after possibly lines of confrontation and belligerence and there is now, apparently, no explicit civilizational divide, no religious underpinnings, no cultural challenges either (although one cannot help that the Palestinians and many other groups in the Muslim world are not top of the agenda). Doesn’t the capitalism bring dynamism to the engine of these insufficient parts to be sure? Yet, it is the U.S. behind this West and China mostly behind this East and then the blob of former underdeveloped or developing countries in what used to be called “Third World,” the expanding BRICS association missing (i.e. Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). There is no explicit race-and-ethnicity as though such considerations held no importance, but if you read carefully the circle of interpellation for inspiration, follow the statements and the citations, check out the bibliographies, we are dealing in the case of Ikenberry with white-Asian and Black-Brown partitions embedded in this crude spatialization of world affairs in which “Anglo” underwrites the West, which is now not civilization, but “order” as it is instrumentalized by U.S. geopolitical intent.

The old mechanics of “making order” –interesting turn of phrase—appear dysfunctional. Ikenberry signals the San Francisco moment of hegemonic rule-making after WWII. There were no references to Iraq war or the UN resolutions around 9/11 and, of course, Israel never once came up. Ikenberry established two types of groupings for the immediate future: coalition building of like-minded nation-state entities and competitive rule-making in between the U.S. and China. The language is calibrated and vague, flexitarian, adjustable and binary enough to mark the distinction that matters most (U.S. and China). Ikenberry avoids the language of “great powers,” perhaps he sees that as realist purchase, but such big-unit demarcation is explicitly implied in his arrangements. The talk of the “West” remains, perhaps surprisingly, yet it is the “Western Liberal Order” variety, and one wonders whether we should see a bold uppercase or probably a more modest or coy lowercase typographic use as in The Guardian and other outlets. We are not talking about the big history of Western civilization as in Arnold Toynbee, which still included incisive self-criticism. We are talking about “the U.S. and its allies.” Ikenberry said that “the West is finding itself again,” thanks to Putin (I think he was mentioned once, unlike Xi Jinping, none). The political formula of the external point that helps unite cooperation is being tried.

Hobbes must have been smiling his Gioconda smile in some funny place. Although he was not mentioned by name, I felt his presence in Ikenberry’s “liberal” vision of immediate tensions. No single historical figure was invoked for inspiration, except the FDR’s state official whose name, I think, was Cordell Hull. You get the idea of the general path taken, past and forward. The “age of insecurity” as in the conference title –which kicks off here not in the Iraq war but say, 5-to-10 years ago, covid on top-- finds the desire for security coalition-building of the like-minded entities in Ikenberry’s future-oriented political imagination strictly within narrow American confines (Democratic administration of the state apparatus and Ivy-League academic collaboration) increasingly under extenuating circumstances. These do not appear to make him change his modus operandi that has remained steady at least since his Princeton hiring by Slaughter. The rest of the “world” matters not at all as far as knowledge production is concerned (the totalizing disposition is his own self-assigned preserve within such rarified West, the other parts might as well provide their desired particularities, but will never be allowed to mount a blowback totalization that brings instant “cultural relativism” to our IR scholar). The vagueness of these slogans is easily peeled away: it is the U.S. who owns this West and it is this coalition of the willing that makes the rules. Tellingly, Ikenberry mentioned that this “West” is not a geographic concept, that it is a “concept of order.” We move away from brief descriptions of capitalist forces, particularly those that are doing damage inside American society, and we are in the seemingly more spacious domains furnishing world visions. It is wise not to fall under the spell of such uncircumscribed timespaces. No slices: nothing will serve G. John Ikenberry except the big pie of the global world. Uncle Sam always gets the biggest slice. Interestingly, it is the other “competitors” (China and Russia) the ones who are expansionist and revisionist now.

“Liberal” is always a good marker in these venues. There are no mixtures: “illiberal” is a term of abuse, the opposite number, the “not-I” of the speaking subject, the Other, the phantasmatic nation-state of competitive might that is always already faulty, wanting, “autocratic,” “belligerent,” etc. The binary is crude, the Manichean disposition of the rigid dichotomy puts the speaker in the “force for good” versus ghosts of others who are typically never sharing the proximity in the same platform on the presumption of equal worth (it is almost a “gossip structure” in which I talk to you and you talk to me about a missing “them”). We are not dealing with sophisticated allegories of virtues and vices as in the Baroque period. We are not even dealing with one, two or three national allegories of the former “Third World” either. The set-up is closer to some kind of Steven-Spielbergesque Hollywood-like tale of the world with the good American-character identified with the good superpower is in the main action and center stage or plot and the “sharks,” monsters or evils of this world are lurking in the background, something like pantomime and fairy-tale apparitions. I cannot believe how much of this type of staging is put on display time and time again also in “respectable” academic matters of international relations, the foreign humanities and the typical mass-media coverage in the still hegemonic Anglo world. The LSE was not rich in imagery. It delegated such duties to one humble and foreign scribe who is about to be identified.

Yet, it is these “illiberal great powers” that are said to signify, or represent, a challenge to the “rule-based expansionary concept” [of the US-dominated “West”]. We must handle with care such slogans built around a generality devoid of cultural-specificity or timespace circumscription. Good collaborations of the types Ikenberry had in mind: the so-called “Quad” [Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, of QSD, of India, Japan, Australia and the U.S.], the “Atlantic grouping,” i.e. NATO, and he also mentioned the G7. Interestingly, the European Union was not mentioned. Neither were the United Nations, either General Assembly or Security Council. International Law and its organisms are always missing in action with Ikenberry who is no partial to international law or human rights. Brexit remained under wraps. Not for the first time, our IR scholar donned Hobbes’ clothes of military alliances to counter the growing influence of China and the current violent challenge of the Russian Federation in Ukraine. Ikenberry conceded that the U.S. is not opening its markets after “70-odd years of leadership.” He is now looking, worryingly, at the signs of the debilitation of such leadership, which he will do his best to revert. His speech had no economy of relationship and care, no non-belligerent international community-building that may push such U.S. leadership down the leadership competition, no need for introspection, let alone contrition, in the provision of wider international vistas and genuine dialogue with a bigger number of interlocutors. No warm xenophilic sunlight ever shines on our noted IR scholar. I wonder what would crack open the closing of this all-American mind.

Perhaps there is something like an embedded coloration of the planet in the previous world triad: three in one, perhaps going separate ways, perhaps converging in other ways. No Vasconcelian “cosmic race:” white, yellow and brown-black are at large since we are largely talking about the US-Europe, add a portion of the British-Commonwealth countries and one or two defeated Asian countries in WWII (South Korea and Japan mostly, to counter the rise of China), and the primary palette somewhat works in the hands of Rachman and Ikenberry. There is also the “bright yellow,” and I am being facetious, of China inside great Asia –and Russia will be have to go underneath the Eurasian of Asian characteristics. Predictably, last in line is the brown-black of Latin America, Africa, Middle East, the Pacific-Oceanic islands, etc. never quite coming out the smokescreen, haze or fog, let alone academically or intellectually speaking. I think the three-color palette works, add “red” for “indigenous” dovetailing with under-represented groups and this type of liberal internationalism constructed around the explicit empty-subject-position inhabiting an indistinct time-space of splendid isolation soars over all of them, at least in Ikenberry’s vision which is always American, how could it not?, if planted, metaphorically speaking, in the vicinity of the so-called Western nation-states of the North Atlantic. His history extends from, say, the mid-to-late 19th Century to the “proper” US supremacy after WWII, as it passes through the various stages of (post-)Cold War, Fukujama’s “end of history” (there is a Princetonian collaboration between Fukujama & Ikenberry), now going through the motions of post-Iraq/Afghanistan, Biden after Trump after Obama after Bush 2 after 9/11, Covid on top, Russia & Ukraine and Gazaj & Israel. It is not a pretty picture.

The inner core must remain, for Ikenberry, Washington and its corridors of power and influence with exclusive circles in the Ivy Leagues and other “coalitions” (Chatham House, LSE on the London platform, etc.). I am yet to catch a free-thinking European-Union representatives in these spaces. There are outer domains: the Global East (China and Russia) that is now reaching out to the Global South, the tertium quid that must be “co-opted.” Such monstrous latter unit –lacking proper names and capitals and seemingly traditions of thought-- is not “making choices and not uniting to make choices.” The question they are asking is, “what is in it for me?,” ventriloquizes Ikenberry as though the question could not boomerang to hit him too. You can almost feel the distancing from the so-called Global South as though it had to be handled looking elsewhere, holding the nose and with a ten-foot pole. Yet, these three parts are said to be creative and dynamic, but also relatively stable. We know where the speaker stands. The language that emerges is one one of mutual vulnerability, risk management and technocratic functioning. The thrust is reformist. Things must not change too much. The display is also without a glimpse of Gattopardesque elegance that is not deemed needed.

David Luke (LSE) referred to some general data about Africa, thus in toto, inside what he called the great differentiation within the Global South: 60% extreme poverty in Africa and 2% of world exports. Africa is not converging with world economy and its exports are mostly going to the EU, China and the U.S. is well below them. There was greater circulation inside Africa. There was nothing political per se in his discourse that made Africa look somewhat small at least in my eyes. Nita Rudra (Georgetown) turned out to be in essence a promoter for revamping globalization. Does not “global” do the same job? She wanted to go against a tendency to continue interrogating it, and even rejecting the term. Rudra advocated the renewed education of those who think that way and the recommitment to globalization share the call for a shared prosperity and social investment. I heard universal echoes in this general-business perspective. Surprisingly, she concluded with a quote from Pope Francis about how to be “at the service of all.” Was it the Jesuit institutional calling in the city of Washington? In this religion-free setting, it felt out of place, given the pro-general-business frame of things going the American way. Or perhaps I am misreading an underground congruity.

Nuancing matters, also in the Q&A: Ikenberry put the binary of the multi-pluri-national organizations and the global-governance, singularity which he would favor. If countries are picking and choosing, then we must be prepared to see a lot of movement in the institutions (for Ikenberry, the actors are exclusively the elite groups of the powerful nation-states starting from the great powers and there are no sustained institutional readings, let alone his own). If the Bretton Woods system constitutional moment is now broken, and one may well wonder since when, we appear to be moving away from “trade liberalization” at least for a certain period. Ikenberry added that “Jake [Sullivan] knows.” We are heading for “a relative rule-based order” (my emphasis). Let us underline the crucial adjective within the under-developed nominalism of “rules.” Do we mean laws, principles, standards? One thing is certain: Ikenberry is not considering rules broken by the U.S. or given by others to the U.S., for example the U.N. or the International Criminal Court of Justice, which were not mentioned. The talk of human rights went typically missing. The talk of international law or crimes against humanity: you already know the answer. This is not the type of multi-perspectival internationalism favored by Ikenberry’s liberal internationalism.

If we inhabit the post-liberalization agenda, there is, Ikenberry said, some platform for “negotiation.” The noun was recurrent, generic, open, empty, an uncircumscribed euphemism, over a family of options (supremacy, hegemony, coercion, co-optation, etc.). Negotiation is a polite, noncommittal option for politics, the cloaks to the daggers so to speak and we are in the geopolitical realm of knowledge-and-discourse production in settings in which no inch is given to the so-called “global East” and the “global South,” by the “US and allies.” Epistemic nationalism, myth of “splendid isolation,” or even, why not?, the jingoism of suave manners under the guise of liberal internationalism (I missed Mearsheimer’s sincere directness). The ugly side of such realm is not something in which Ikenberry dwells publicly (no negotiation is ever detailed, goes wrong, is born out of coercion, Uncle Sam is never taught a lesson, etc.). There is instead quick finger-pointing at the “competitors” and that will do. One good question posed by Ikenberry, “where does the negotiation platform exist?” Not on that LSE London conference.

The World Bank was no option. No United Nations either. The slogans appear rusty. They have lost their color. The rules will be “negotiated” inside “like-minded coalitions.” Ikenberry’s explicit desire, which we take at face value, is not to want to go for the apparent road taken of an economic nationalism under the leadership of his nation (I must insist on the naturalization of the epistemic nationalism in which “America” is the sole purveyor of IR knowledge from the beginning of time to the end of time). I have felt for a while that Ikenberry is approaching Samuel-Huntingtonian positions of conservatism understood mostly as institutionalism. I remember Stanley Fish’s Trouble with Principle proclamations at Duke University in which “principles” are at best misleading statements since they are contingently embedded and always interest-driven changing according to circumstances. Something of this principle-shyness is now at play in Ikenberry who is sounding more “realist” than “idealist,” “good cop” to the “bad cop” when he sets up simplistic partitions when others talk the talk of strategy, tactics, nuclear power and kinetic dynamics in the theaters of war.

This is another way of saying that circumstantialism is now what, in my sense of things, rules Ikenberry’s IR thinking. The recent past –since Woodrow Wilson—may be good, for the likes of Ikenberry. This past has crumbled (see my interview for details). The immediate past of “end-of-history” delivered unipolarity and Iraq-War violation of international law and state of exception in the West (Agamben following Schmitt) and we are now living in the aftermath (Russia, Ukraine, Israel, Gaza). The logic is one in which “if the big cat behaves like Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib and commando activity in Pakistan, etc. the smaller cats will do something similar in the areas where the cat is missing, Syria, Ukraine, Gaza, etc.” The recent “rules-based order” coinage is, always in binary, Manichean opposition addressed to others who presumably do not follow rules. But this is a desperate attempt to camouflage the US hand the rocks the cradle of a subordinated non-US world that is not willing to go along, discursively and not discursively. Rules or principles or laws or are we falling for non-specificity and casuistry?: it does not wash. “Liberal” is the adjective that sanctions the preference of the subject-position identification not with the silenced institution (Princeton, turned into a handmaiden) but with the U.S. nation-state and superpower apparatus and here also with the philanthropy of big business not in Colorado or California but in London. The “illiberal” others live in a big hole or abject lack. Ikenberry’s IR binary logic remains American-Manichaean. It does not contemplate plurality. It will not pursue idolatry. The English-only bibliography of Ikenberry’s books does not welcome challenges to such logic. The platforms he tends to occupy, LSE London is one, do not challenge him in the slightest. If this circumstantialism has, I feel, always been there lurking in this IR modality, there is also undeniable cynical play in the self-assignation of virtues. Once “principle” goes out the window, this IR business may gently remove the mask of the West and show in good faith the propaganda fidei of supremacist Americanism.

“Optimistic” future projection of big Area-Studies even if undergoing reconfigurations is a must in public events of this nature. The totem and taboo will be the “force-for-good” of the US-position. This one is, almost prudishly, presented with the fig-leaf of the West, whether in upppercae or lowercase, now adjectivized as “global,” which is conveniently clarified for those who remain very distracted, as “U.S. and allies.” Lovely lack of specificity (read irony in the adjective, please): inclusion and exclusion mechanisms may open and close waterways depending on the circumstances. The UK remains reliable “all-purpose equerry” as Perry Anderson put it, the Europeans will fall in line when chips are down, or at least this is the calculation of these liberal internationalists who cannot afford to lose the European horizon. But it is the Europe of the North Atlantic, to be sure. Language of (human, women’s) “rights” emerges and disappears. It was missing at this conference. “International law” is even less common. Terrorism was not mentioned, state terrorism even less. But our platformed presenters will not linger there. “Crimes against humanity” is almost exclusively associated with National Socialism during WWII, at least in these official circles. It may emerge strongly again, if slowly in the mainstream Anglo media following early denunciations elsewhere, Aljazeera for example, about the Middle East, fractious, fractured area-study not quite fitting into the triangle furnished by Rachman and Ikenberry.

Proclamations about the desirability of open markets and greater investments in the workforce sound like desiderata without the necessary embodied stigmata or pain. If history is pain, as one saying has it, there was none of that on display at the conference. The participants did not appear to bleed on the side of workers’ Unions (first speaker did not put these on the side of technical innovation). The equation (globalization, shared prosperity, social investment) went in the non-specific, universal direction. I did not see any vertebration of those conventional-enough expressions of desire that would have been substantially different from the Biden administration. I do not recall one single successful example of such conference slogan in relation to any city, region, nation, America or not. Eyes seemed to be for Polyphemus, the U.S., qua mighty nation-state superpower and this appeared to be mostly about how these speakers could put such wind in their sails or wings and fly away from London. The ghost of the United States National Security Advisor (Jacob Jeremiah Sullivan), and not the one of the 71st United Sates secretary of state (Antony John Blinken), seemed to be on the receiving end of the telephone of these speakers’s suggestions for good policy, which now apparently unites domestic and international. No other state official of any other current or past government was mentioned.